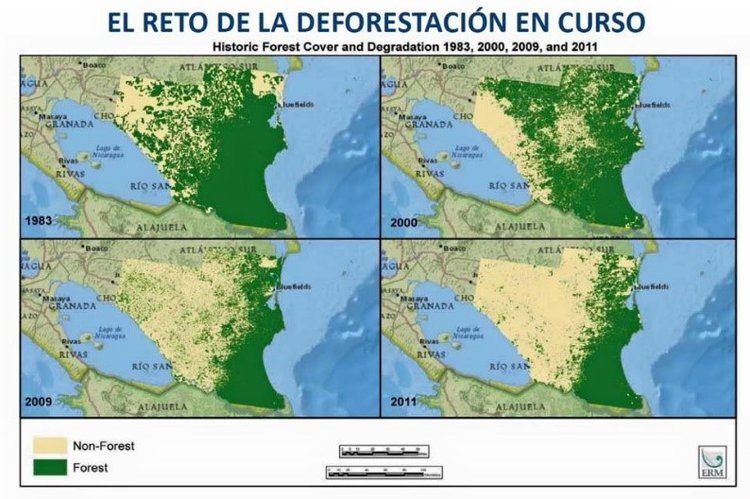

Water is life. But across Nicaragua, rampant deforestation for cattle, agriculture, and timber extraction is causing water to become scarcer.

Community wells are drying up in deforested communities in the country’s northern and central regions, leaving villagers without a source of water. Streams that once flowed year round are now seasonally dry. Follow the remaining upland streams and you’ll end up in denuded hillsides where row crops are grown on steeply sloped ground and cattle are king, roaming wherever they please.

Cattle ranching and agriculture have replaced natural forests. In Waslala, Nicaragua, loggers cut down a third of the forest over 23 years. The effects of deforestation are already being felt with warmer temperatures reported and at least a 32% decrease in water flow over the last 5 years. Deforestation continues at a rate of at least 1% per year. High debt in the 1980s led to more timber and agricultural production while lax laws in the 1990s resulted in timber companies having greater access to forests. Laws have now changed, but enforcement is low so illegal logging and colonisation is rampant [1]. It is estimated that 50% of logging is illegal. Traditional slash and burn agricultural practices have left the remaining soil thin and deficient of nutrients.

What is the impact of climate change?

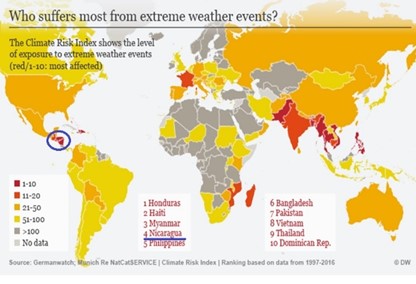

Climate change compounds the problem. Nicaragua is a minor contributor to global climate change yet will be significantly impacted due to location, coastal borders, and dependence on agriculture. On a global index, Nicaragua is ranked fourth most likely to suffer from extreme weather events.

General trends that can be predicted confidently due to climate change are:

• rising temperatures

• increasing drought in Central America (10-20% predicted reduction in rainfall) [2]

• less stable growing conditions for crops resulting in lower yields

• increase in extreme weather events

• rising sea level, inundation of coastal communities, and the salinisation of wells in coastal areas

In an area where most people are subsistence farmers, this puts food and water security—and residents’ existence—at risk.

El Porvenir’s Watershed restoration program

The situation is dire and watershed restoration is essential to save the future of water in Nicaragua.

El Porvenir’s watershed restoration program seeks to conserve existing forests and restore degraded areas throughout Nicaragua to increase food and water resilience. To improve land use and mitigate climate change, we are actively implementing the following watershed rehabilitation practices, many of which have been used for generations:

1. Strategic reforestation where trees are integrated with livestock and crops to create a sustainable land-use system that rejuvenates damaged land while restoring stream flow, increasing rainwater absorption, and reducing soil erosion. Native grasses are used to reduce erosion, and family garden plots are established.

2. Construction of terraces and other water conservation infrastructure like check dams and seasonal retention ponds, fencing off areas that are being regenerated, growing grass to feed cattle, and constructing watering troughs away from streams.

Multiple benefits of seasonal retention ponds: trapping water forces absorption into hardened, degraded land AND the water stays long enough to use a simple irrigation system to grow crops like beans and corns in the dry season. This improves food security and improves farmers’ income as they can sell off-season crops at a higher price.

3. Construction of vented, fuel-efficient stoves that use 60% less firewood than typical stoves to reduce deforestation and improve health.

4. Coordination with local government and other organisations to increase impact.

5. Educating residents on the economic and environmental benefits of climate change mitigation and watershed restoration through community workshops.

6. Creation of a model watershed that uses all of the above practices to show people from other communities how their watershed could flourish.

7. Training residents to create local community management committees who manage and maintain systems and programs. The training and education of residents to promote behavioural change is a pivotal part of conservation, restoration, and protection.

Conservation and a community-based approach

El Porvenir promotes a culture of conservation. Forests are reservoirs of biodiversity: critical refuges for numerous ecosystems that provide carbon-storage to buffer the effects of the climate crisis. Our work educates residents and involves them in watershed restoration to promote plant and animal diversity in a way that creates a better standard of living. Making these changes now will reduce the impact of extreme weather events in the future. For example, a community with forested hillsides is much less likely to experience a devastating mudslide than a deforested community. We work with communities on risk management: building systems to resist negative impacts of heavy rain, drought, and other weather occurrences.

Agricultural practices must adapt to warmer temperatures, reduced precipitation, less secure water supply, more extreme weather events, and more aggressive plant diseases and pests. To improve water supply and food security for future generations, we will continue to restore upland watersheds and work with villagers to implement sustainable management practices that support traditional agricultural activities while making those practices more sustainable.

All our projects begin at community level with rural Nicaraguans asking us to work with them. The people most interested in this program are those who feel the effects of poor agricultural practices and climate change on their crops. Our rural partners have lived in these areas for generations; they know weather patterns are changing, temperatures are rising, and water is becoming scarcer. What they don’t know is how to reverse the effects of generations of poor land management and climate change. But they want to learn. El Porvenir’s watershed program provides a critical bridge between rural communities in Nicaragua and their future sustainability.

You can support El Porvenir’s work by making a donation at elporvenir.org/donate.

[1] Nicaraguan colonisation: we are not referring to the Spanish or British colonisation of Nicaragua, but rather colonisation that is ongoing . Nicaragua is made up of sixteen departments (western Nicaragua) and two autonomous regions (eastern Nicaragua); there is tension between the two sides. The autonomous regions are sovereign territories with little transportation or communication infrastructure, minimal social and economic investment, and low coverage of basic services. Waslala is located in the northern autonomous region. Though the autonomous regions have sovereignty, non-indigenous people from western Nicaragua have been settling, often illegally, in the autonomous regions.

[2] Dr Richard H. Gammon is Professor(Emeritus) of Chemistry and Oceanography, and Adjunct Professor(Emeritus) of Atmospheric Sciences at the University of Washington