The Sanitation and Water for All Partnership (SWA) High-level Meetings (HLM) happened less than a month ago in Washington DC with a focus on how to finance the achievement of the water, sanitation and hygiene-related SDGs targets by 2030, including how to strengthen the sector and reach universal access.

Sector ministers and finance ministers discussed this crucial topic on two separate meetings on the 19 and 20 April. Around 60 governments attented the meetings. The other partners of the partnership (International institutions, Civil Society Organisations, Private sector, Research and learning) were also present.

End Water Poverty (EWP) was part of the Civil Society Organisations delegation gathering 10 CSOs representatives from from Africa, Asia, Latin America and Europe and the USA. The CSO delegation had an important role in sharing the CSO messages, facilitating interactions, and reporting on the main discussions to their regions.

EWP’s Water Action Month webinar series, which were held a month prior to the SWA High-level Meetings, covered the topic of Finance, and welcomed a holistic panel of six speakers from various organisations to address the complex question, “How to Finance an End to the Water and Sanitation Crisis?”.

The general consensus across the panel was that the WASH sector is often seen as an infrastructure sector. This common vision has a real impact on how the sector is financed

Each speaker brought a different approach to advocate for a new vision of the WASH sector which could allow for a shift in how the sector is financed.

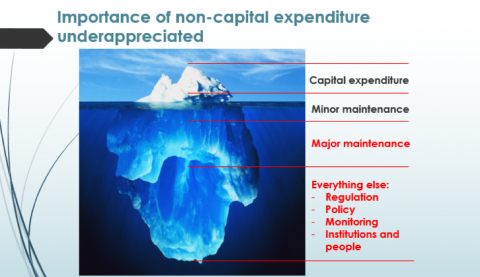

Catarina Fonseca, from the think-and-do-tank IRC, highlighted the insufficient attention to the rest of the system. As the water and sanitation sector tends to be seen as an infrastructure sector, the importance of anything that is not capital expenditure has been systematically underappreciated. Therefore, this focus affects the rest of the system that is actually needed to make the infrastructures functioning. There is not enough attention to the policy, the regulations and non-infrastructure pieces of the system and consequently to the most vulnerable people and their needs. Current sector investments, especially in the poorest countries are scarce and poorly targeted. Catarina Fonseca opened the webinar by underlining the progress towards the SDGs, quoting the Joint Monitoring Program’s recent report. It shows that more than one third of countries are not on track to achieving universal access to safe water by 2030. Billions of dollars invested in infrastructures become non-functional after a few years because of failure to set up maintenance in the system and keep water flowing.

The Joint Monitoring Program report also shows that significant disparities remain between the richest and the poorest in rural and urban areas, and that there is no correlation between investment in water supply and sanitation and the area that have the lowest coverage. The result of this is that investments tend to favour the better of. Catarina Fonseca advocated that to make progress, a radically new financing approach is needed in the sector. If private sector money is needed, then investigating public money in the systems needed to make those investments a good bet is absolutely critical. Based on the example of countries such as in US or in Europe where universal access been reached, she argued for a double role of the State for improving the sector. States have to provide leadership to the sector and establish a strong service authority that could regulate and monitor the sector. If private money is needed, then investing public money in the systems needed to make those investments a good bet is absolutely critical.

Picturing the difficulties of the WASH Sector, she advocated for a shift in the way that the sector is being financed, and specifically advocated for more accountability from donors and Governments in tracking finance for the sector. There is a need to really understand what are all the real cost of services and how long investment are really lasting and where the financing is going.

Susan Davis added to Catarina’s conclusion with a comment on the way funds are allocated in the WASH sector. Her organisation, Improve International, conducted a survey in 2016, endorsed by 100 civil society organisations (including a few donors), to study how WASH donors influence sustainability. Most of the survey’s respondents indicated that they believe the way donors fund, influences the sustainability of WASH services. They almost all agree that the way money is allocated affects the outcome of the programs in question. This survey also showed that a majority of the actors who provided feedback, think monitoring and post-implementation research, professional development, and management, is underfunded. Susan Davis outlined that most of the donors seek concrete results, and want to physically see what their investment generated. She advocated for a shift in funding towards different aspects of WASH investments, which would in turn need for donors to have a better knowledge of the costs for a sustainable project.

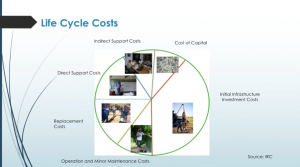

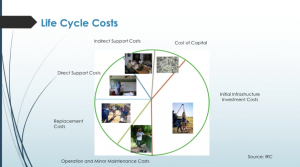

Kim Lemme clarified well the issue of financing sustainable services by highlighting the importance of budgeting and knowing the full life-cycle cost of a service. In doing so, she emphasized the importance of focusing beyond initially building infrastructure, on other pieces that keep the water flowing over time (e.g. support costs, maintenance, replacement). Here is the Life Cycle Costs depicted by IRC.

This diagram shows the part of the initial infrastructure investment and what are the other costs for a sustainable service:

- Operation and minor maintenance costs is what is needed to be done to keep the small pieces working that keep the all system working;

- Replacement costs need to be planed and budgeted;

- Direct support costs: these investments are mostly made by the service authority, (local government or a wash office in the municipality). There are not huge but if they are not done properly they can break down the system.

- Indirect support costs include the advocacy and actions that help at the national level to make sure that everything goes properly at the local level.

- Cost of capital: a critical component of WASH projects is the costs associated with acquiring the necessary capital for building and maintaining the new infrastructure.

Water for people developed a toolkit for local governments and WASH project managers to evaluate and analyze the global cost of a service and to budget it. Planning and budgeting are key components to implementing sustainable services. To conclude, Kim Lemme also put an emphasis on the need to increase responsibilities: clear delineation of roles and responsibilities, especially for service authorities and service providers, are key to success.

Heloise Chicou, Civil Society Organisation (CSO) Advisor for SWA, underlined how the ongoing discussions at the international level through the multi-stakeholder platform Sanitation and Water for All and the High-level Meetings addressed the the need to improve the financing for the WASH sector, and the need for additional funding to achieve the SDG 6. The feasibility of achieving the SDG WASH targets depends on using the current funds more efficiently and the ability to mobilise and redirect significant additional resources, beyond historical levels of expenditure. According to the World Bank, the total capital investment to deliver universal access to safely managed WASH around $114 billion per year.

The SWA Partnership, through identifying the bottlenecks in the sector, has pushed forward an approach (the Collaborative Behaviours) that is not a project approach but an approach where government and donors work together to improve the system. They focus on

- Enhancing government leadership of sector planning processes,

- Strengthening and use country systems,

- Using one information and mutual accountability platform,

- Building sustainable water and sanitation sector financing strategies.

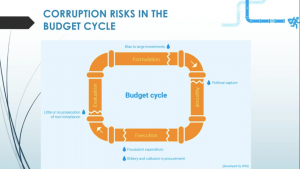

Lotte Feueurstein from the Water Integrity Network also highlighted an important bottleneck responsible for low efficiency in the WASH Sector, and limited trust from funders: corruption and lack of accountability and transparency.She described the corruption risks in budget cycles in public financing mechanisms:

Key points from this cycle are:

Corruption can give preference to large scale investments because they are more likely to pay back than small decentralised investments;

Political capture during the approval process: members of parliaments who are voting can serve their interest group before general interest.

Once the budget is approved, the execution phase is where corruption risks are the highest. WASH competes with other service sectors (education, health …) and local decision makers can choose their preferred sector which may leave WASH projects high and dry. Further, bribery and collusion might influence procurement of services.

It is not always the case, but evaluation should be happening at the parliament level, and what is even more complex is that even if corrupted activities are detected, there are political interferences that lead to no prosecution.

Complementary to the SWA 4 collaborative Behaviours, the WIN promoted 4 pillars that Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) should seek, for an improved sector: transparency, accountability, participation, and anti-corruption. The Integrity Wall below is a model on how CSOs and other actors can strengthen integrity in water sector financing using these 4 pillars. To have an impact, lobbying at the parliamentary level is efficient as the parliament committees can have influence on the detailed budget.

Lotte Feuerstein presented the example of an NGO coalition in Mozambique who successfully lobbied their Parliament, by forming a coalition of different sectors of services and providing a technical position paper with clear requests concerning all types of services represented by the coalition.

Kate Fogelberg from the Springfield Centre also presented the influence that NGOs can have on the sector and gave an input that could help answer the need for additional finance. She explained how NGOs can contribute to increasing efficiency and attracting new funding by using a “Market Systems” approach. She introduced the concept of Non-Revenue Water (NRW), which is the portion of water that is distributed which gets lost before it reaches consumers (either through leaks or theft). Globally, half of all water is lost as NRW, an obvious massive inefficiency. It disproportionally affects the poor since they are not connected to the system and as such they are the first to be cut off. Neither governments nor donors prioritise funding a decrease of NRW, but the issue could be leveraged to attract new funding. So if funders were looking at this NRW in terms of demand and supply within the “Market Systems” approach, they would understand the potential huge benefit of investing in NRW.

Kate advocated that there should be a shift towards funding a redesign of the system. She illustrated this via a case study in Kenya where, instead of ‘classic’ financing of infrastructure, stakeholders financed a wider rethinking of the system. They used funds to re-evaluate the system and to finance new domestic financing mechanisms. Early results are positive, as this initiative has improved service providers’ efficiency by using NRW and attracting new financial funding, and in turn has increased the bankability of the sector.

All panelists agreed on the need for a shift in financing mechanisms for the WASH sector towards focusing on the whole system, including costs beyond infrastructure, and providing funds to achieve universal access. All stressed that CSOs have a role to play in influencing and working alongside decision-makers towards this shift:

Heloise Chicou explained that CSOs can play a role in improving sector performance and the financing of SDG 6 on access to water, hygiene and sanitation by:

Developing strong advocacy at the international and national levels to have adequate financing and financing national strategies for an inclusive and transparent implementation of the SDGs,

Making sure that financing respects the human rights to water and sanitation and call for a respect of the core principles of Human Rights – such as affordability and sustainability.

Being the watchdogs and ask their governments to be accountable by making national and local budgets provisions to be available to the public and transparent.

Monitoring and tracking budgets to make sure they provide for the poorest

Participating in budget definition and orientation through requesting for participatory approaches.

The challenge for the CSO delegation attending the High-level Meetings was to make the voice of the CSOs heard to advocate to the donors and governments for a strengthening of the system, more transparency, more accountability and a “leave no one behind” approach.

The SWA CSO constituency identified key messages that they shared at the 2017 Sanitation and Water for All High-level Meetings in Washington.

The High-level Meetings are an important opportunity to make those messages heard, but they are only one part of the overall work that Sanitation and Water for All assumes. The key issue here is to act towards strengthening the dialogue at the national level and strengthen national systems on the long term.

To listen to the full recording of this webinar session, please click here.