Drought, disease, dissolution, death – these are the stark realities of life without safe water.

Quality of life, health, and hygiene largely depend on safe drinking water and sanitation. Yet in many areas of rural India these fundamental human rights have not been realised – especially among poor and marginalised communities. Odisha, as one of the least progressive states in the country, needs more attention than most.

How safe is the water we drink? The latest report by the Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation of the Union Ministry of Jal Shakti indicates that drinking water is contaminated in 15 of Odisha’s 30 districts. During the peak of summer, many villages in the state’s coastal pockets experience acute water scarcity owing to the exploitation of groundwater and the ingress of saline water. In several villages groundwater levels have subsided one to two metres below normal. The situation is even worse in the highlands, forests and tribal areas.

Tribal communities face serious drinking water problems. Government data shows that of 85,600 Adivasi habitations, only 56% of are covered by rural drinking water supply. Tribal communities are also inadequately represented in public bodies, while mining and other industries severely affect their drinking water sources.

In the absence of proper sanitation facilities, more people in Odisha are forced to defecate in the open than in any other developed state. Many people wait until late night or early morning to relieve themselves. This practice compromises women’s privacy and dignity. Children, sick people, elderly people and pregnant women experience various problems in the absence of proper sanitary facilities at home. Many schools also have no toilet facility.

Water and sanitation are the state’s responsibility. Odisha State Government has not adequately invested in the sector and is yet to outline a water and sanitation policy, leaving people to languish in extreme poverty, landlessness, illiteracy and social discrimination. Recent trends show that the water needs of industry, mining and other commercial ventures are prioritised over the needs of common people. While privatisation of water services and increasingly polluted drinking water sources affects society’s poorest, the government has shifted responsibility to market forces and encouraged public-private-partnerships in the water and sanitation sector. This will further deprive people of access to safe drinking water and sanitation.

Many people’s movements and organisations have raised this issue with international human rights bodies, the Supreme Court of India and a number of High Courts including Odisha’s. On various occasions the government has been reminded of its primary responsibility to ensure water and sanitation as a human right and constitutional guarantee for all its citizens.

Poor and marginalised communities should receive free access to drinking water and sanitation without discrimination. Yet even today thousands of Dalit women in rural villages have to queue at wells and tube wells to collect water, waiting their turn after caste Hindu women, who wash the tube well to avoid ‘polluting’ themselves by touching the same surface as Dalit women. Despite civil rights law enshrining discrimination-free access to village water bodies, many people face indignity and social humiliation every day just to access drinking water.

India’s Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation has implemented programmes like the Total Sanitation Campaign, Nirmal Gram Puraskar, Nirmal Bharat Abhiyan, Swachh Bharat Mission-Gramin, Swajal Dhara, Basudha and National Rural Drinking Water Programme. Despite several plans and programmes, millions of people still live without safe drinking water and sanitation. Odisha State Water and Sanitation Mission, formed in 2002, has been ineffective in reaching rural and tribal areas.

The traditional approach of providing services like building toilets or drilling boreholes has ultimately proved to be ineffective in achieving transformative change and universal access to water and sanitation. A Rights-Based Approach (RBA) shows promise of being more effective in holding the government accountable to existing laws, rules, regulations, and orders issued by competent authorities such as legal institutions like courts and statutory bodies.

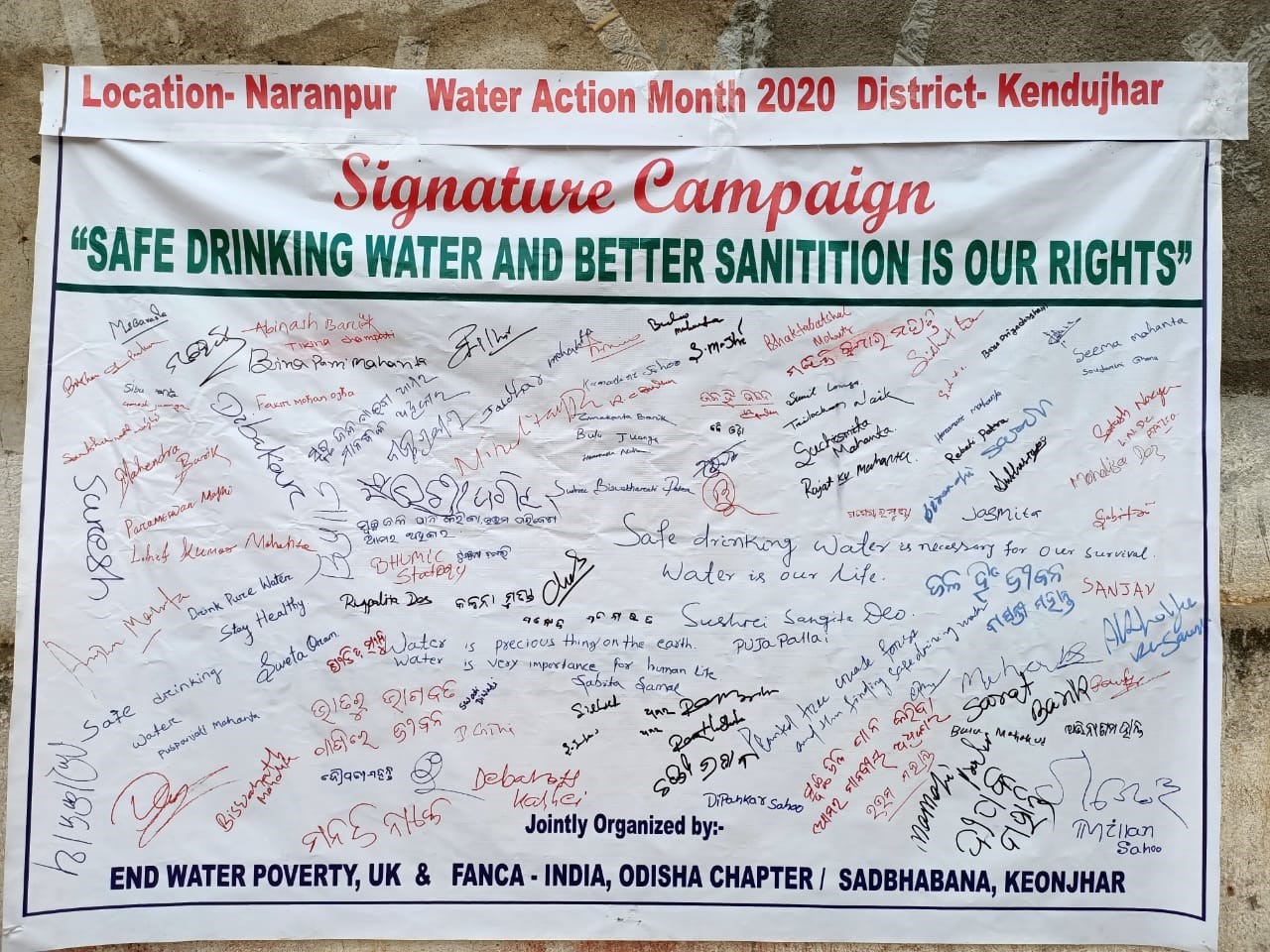

Communities – especially marginalised groups and civil society – need to start proactively lodging complaints, representing themselves, or creating postcard campaigns to hold their government accountable. In March 2020 the Indian Institute of Youth and Development (IIYD) joined End Water Poverty’s Claim Your Water Rights campaign.

Our objectives:

- To identify the issues experienced by marginalised groups in Odisha

- To ensure the voices of marginalised groups are heard by different commissions

- To sensitise duty bearers to provide better services and to fulfill the rights of deprived communities

- To start a water rights movement among marginalised groups in Odisha

After collecting information at community meetings, it was unanimously decided to escalate the water and sanitation issues faced by marginalised groups to different commissioners and local authorities through postcards and mass representation. Marginalised groups like women, tribes, children and senior citizens participated in this process. In collaboration with six local partner organisations from IIYD and Freshwater Action Network South Asia (FANSA), 15 representatives from seven districts submitted complaints to various commissioners, including the Odisha Human Rights Commission, National Scheduled Tribes Commission, Odisha State Commission for Women and Odisha State Commission for Protection of Child Rights.

Major lessons:

India has immense cultural diversity so our approach varied from place to place. For example, a tribal community lodged a complaint concerning the construction of toilets in Koraput. A subsequent report showed that the money allocated for the toilets had been spent despite no construction work taking place. The government simply assumed that the tribal community would not complain. When the commission received the complaint, the government had no other option but to start immediately constructing toilets in the community.

The Koraput community now understands the effectiveness of representing themselves. News of the complaint’s success has since spread through the locality. People’s attitudes are shifting from feeling either sympathetic towards government officials or blessed by the benevolence of service providers to feeling a sense of entitlement in claiming what is rightly theirs. Communities and civil society also learnt to follow up complaints with the relevant authorities at regular intervals.

As result of the campaign, seven civil society organisations changed from a service provider mindset to rights-based advocates: educating people on the importance of their rights, lodging complaints, following-up and obtaining justice.